India’s fruits and vegetables (F&V) sector is growing faster than cereals, contributing roughly 30% to the value of crop agriculture. It’s also more nutrient-dense. However, compared to cereals, it receives significantly less institutional support and policy attention. The F&V industry is nevertheless extremely susceptible to post-harvest losses, price breaks down, and seasonal gluts in the absence of well-organized value chains, suitable storage, or sufficient processing facilities.

Around 8.1% for fruits and 7.3% for vegetables are lost in the post-harvest value chain, amounting to 37% of total post-harvest losses of Rs. 1.53 lakh crore annually (NABCONS, 2022). Moreover, with highly fragmented value chains, farmers typically receive about 30% of what the consumers pay for F&V. But what if these small holders join hands and float farmer producer companies, the way it was done in case of milk? The milk story is well known.

Cooperatives under the leadership of Verghese Kurien changed India’s landscape from a highly milk-deficit country to the world’s largest producer of milk with 239 million tonnes, followed by the US at 103 million tonnes in FY24.

Also Read: NIDHI SSP FUND Up to ₹1 Crore

Most more interesting is that companies like Amul claim that 75–80% of the amount paid to consumers goes to their milk producers. For policymakers, the key question is why India is unable to duplicate this F&V success story. It is undoubtedly difficult. F&V contains several commodity value chains, each of which requires specialized infrastructure, in contrast to dairy, where a single product (milk) was efficiently organized. F&V is prone to sharp price swings because it is highly seasonal and frequently concentrated in particular areas.

The only way to stabilise their prices is by integrating farmers into well-structured value chains that includes aggregation, assaying, grading, sorting, packaging, processing, and then having direct linkages in domestic and export markets.

This is where the role of farmer producer organisations (FPOs) becomes critical. Sahyadri Farmer Producer Company Ltd (SFPCL) is one such company operating in Nashik district of Maharashtra, which provides a blueprint for success.

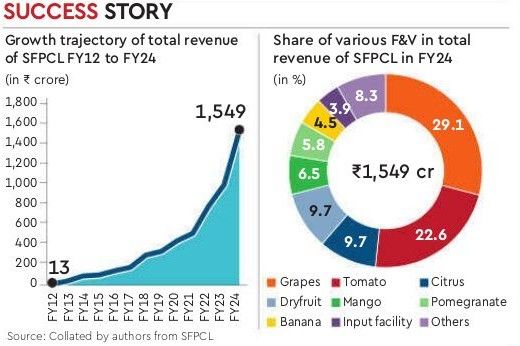

Founded in 2004 under the leadership of Vilas Shinde, SFPCL started with just 10 farmers. It has grown into a network spanning 252 villages, 31,000 acres, and over 26,500 registered farmers in FY24. SFPCL’s annual turnover skyrocketed from Rs 13 crore in FY12 to Rs 1,549 crore in FY24.

The local market accounts for 64.6% of SFPCL’s overall income, with exports to 41 nations accounting for 35.4%. The revenue mix was dominated by grapes and tomatoes (51.7%), followed by dry fruits, citrus, and mangoes (figure 2). Nonetheless, grapes account for the largest portion of total export earnings (63.9%), followed by bananas (12.8%) and mango and other fruit slices (18.2%).

The key to Sahyadri’s success is its capacity to integrate aggregation, value addition, processing, and direct market connections in order to close the gap between local farmers and international markets. Through its solid connections with foreign purchasers, SFPCL has made sure that Indian farmers may access high-end markets by upholding strict quality and traceability requirements and using good agricultural practices.

Also Read: Better Nutrition founders appeared on Shark Tank India

SFPCL is India’s largest grape exporter. It exports 90% of the procured grapes to the European Union and UAE, and farmers receive, on an average, about 55% of the free on board price. Another crucial aspect of its success is its investment in processing infra. Tomatoes dominate SFPCL’s domestic revenue at 35%, with the entire produce going for processing for ketchup, tomato puree, and sauce production.

- This has ensured price stability for farmers even during gluts. Because of the expansion of processing units, SFPCL could generate 6,000+ jobs of which 32% were women in FY24. The success of Sahyadri farms presents a blue print for the entire F&V sector.

As of August 2024, the government set a target of 10,000 FPOs, of which 8,875 had been successfully registered across the country (PIB, 2024). If India can scale up 10,000 high-impact FPOs like SFPCL, it could redefine the F&V sector.

Also Read: This Agri Graduate left his job and started his own Startup